[ad_1]

In his 54 years as a research scientist at Case Western Reserve University, Dr. Arnold Caplan brought it an astonishing $29 million dollars of grant money. He published 465 papers and received over twenty patents. He founded a company, Osiris Therapeutics, that went public and eventually sold for $660 million. But perhaps his greatest impact, aside from his scientific breakthroughs, was on the 150 men and women he mentored and trained in his laboratory. “He was an extremely thoughtful and rigorous scientist who challenged us to think about what he called “the Next Great Experiment.’ He was very demanding but he was also giving in terms of intellectual guidance… His impact will reverberate through a broad community of scientists who he both personally trained and who he influenced by his publications,” said Dr. Scott Bruder, his close friend and former colleague.

Dr. Arnold Caplan passed away on January 10th. He was 82 years old.

Caplan was born on January 5th, 1942, the son of David and Lillian Caplan. They lived in the Wicker Park neighborhood of Chicago. His father, who never finished junior high school, drove newspaper trucks for a living. The elder Caplan was prone to getting into fistfights— even in old age (on his 75th birthday he got into an altercation about a parking spot and was thrown in jail for the night).

He encouraged both of his sons to be tough. As the only Jewish kids in their grammar school, the brothers sometimes had to fight against antisemitic taunts. “His father taught him, in order to get along you had to be willing to use your fists, if necessary,” recalled Caplan’s wife, Bonnie Caplan.

On weekends, Caplan worked for his father, sitting in the back of his truck, stuffing supplements into the newspapers. In high school, Caplan played football and was a good student. “He didn’t show off about being good because it was not cool to be smart,” Mrs. Caplan said.

Caplan attended the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago and majored in biology. He worked hard to earn scholarships. “He had to do well so he abstained from dating. He stayed home; he studied,” Mrs. Caplan said.

After graduating., Caplan enrolled in Johns Hopkins University’s MD-PhD program. He decided against becoming a physician. “You have to deal with people’s feelings,” Mrs. Caplan said. “His mother was a terrible hypochondriac and he didn’t want to deal with that. He liked the intellectual pursuit of things, of figuring things out, so he decided to stay as a PhD.”

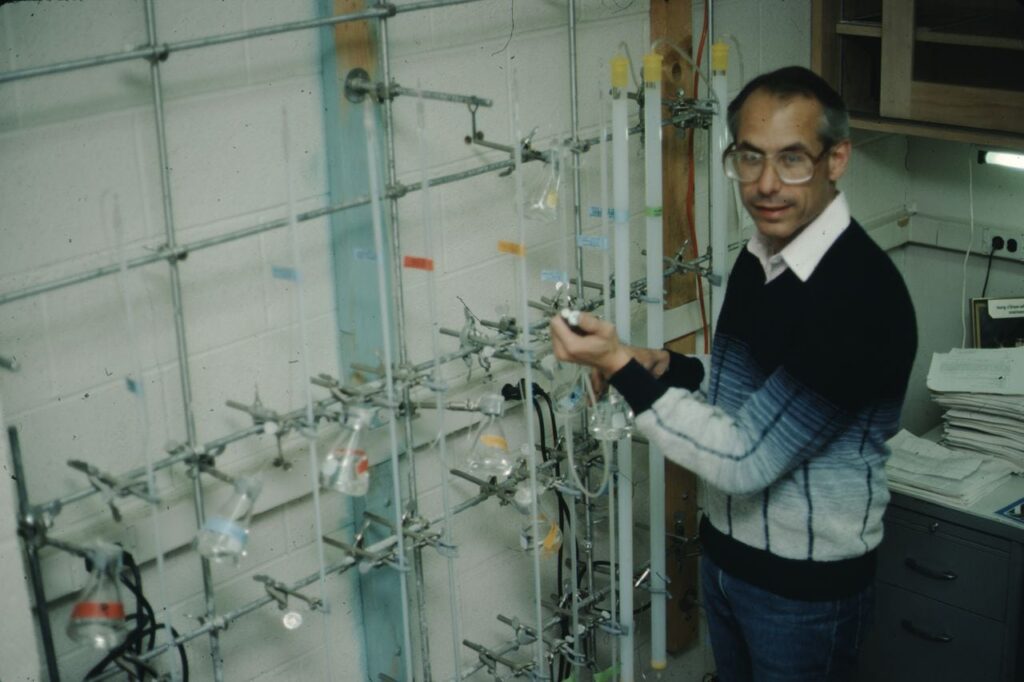

Arnold CaplanFamily archive

Caplan met his future wife when he was home, on break from Johns Hopkins. “He was a nice-looking fellow: dark hair, straight teeth,” Mrs. Caplan recalled.

For a year, the couple exchanged letters while living in separate cities. “The day of our wedding, I had seen him a total of ten times,” Mrs. Caplan recalled. She moved to Baltimore to be with him as he finished his studies.

After completing his dissertation, Caplan embarked on post-doctoral research at Brandeis University. Soon, he began to look for jobs at universities. He got an offer from Case Western Reserve University and traveled to Cleveland to find out more about the position. He arrived in the city on June 22, 1969, the day the Cuyahoga River caught on fire.

The Caplans found a home in Cleveland Heights and settled into their new environs. Caplan began his 54-year long career Case Western. He was an instructor and soon became a professor, teaching biology classes. But the bulk of his was work was in the research lab.

“Science is always changing and he was always learning something new to be able to add to his bank of knowledge,” Mrs. Caplan said. “And so most nights he was working. He was writing a paper; he was reviewing a journal. He was always active.”

After toiling for 25 years in the lab, Caplan made a major breakthrough: identifying and isolating rare cells from bone marrow that he called “mesenchymal stem cells,” or MSCs. He published a seminal paper about the discovery in the Journal of Orthopedic Research.

“He was regarded in this community as the father MSCs,” Dr. Bruder said. “He took great joy in that. He was a dynamic lecturer from the podium and very much enjoyed being the lead speaker around the potential of these cells. People sought him out from around the world for his perspective.”

Caplan continued to study these cells but many years later, he made a new discovery about them. He realized that although these cells behaved like stem cells when in a petri dish, when placed in a mammalian body, they did not.

Dr. Bruder, who worked in Caplan’s laboratory, explained: “Based on what they were doing in the laboratory setting, we were correct in calling them stem cells. But over the next fifteen years we learned that the way they behave in the body, to call them a stem cell is not entirely accurate.”

So Caplan changed his stance and suggested that MSCs should instead be known as “medicinal signaling cells.” Despite not being stem cells, MSCs still had immense potential therapeutic value—in for instance, in their ability to influence tissue repair and reduce inflammation.

“Now there have been a thousand different clinical studies around the world that have assessed the use of these kinds of cells in a broad variety of clinical problems they’re trying to treat—ranging from neurodegenerative diseases, brain diseases, liver diseases, and structural tissues, like bone, cartilage, tendon and ligament,” Dr. Bruder said.

The new discovery proved Caplan to be a consummate scientist, not only in the quality of his research but in his willingness to admit he was wrong when the data suggested it. “It’s a little humbling,” Dr. Bruder said. “That’s important in the evolution of science.”

When not at work, Caplan enjoyed cooking and swimming, which he did daily. He cherished the company of family and friends. “He was funny, warm, and family-oriented,”Mrs. Caplan said. “He was very involved as a father and loved having friends around, having dinners where people sat around and talked.”

He is survived by his wife, Bonnie, his children, Aaron Caplan and Rachel Uram, his brother, Herbert, and six grandchildren.

Arnold CaplanFamily archive

[ad_2]

Source link